In many ways, Franz Joseph Haydn, the quintessential composer of the period of eighteenth-century Enlightenment, is the father of modern music. The forms that he brought to their first perfection are at the center of all ensuing musical thought: the symphony, string quartet, and piano sonata. Haydn was warmly known as "Papa" by his orchestra at the Esterhazy Court where he worked for a good deal of his life, but he has become known as Papa Haydn to us all.

Haydn was born in the town of Rohrau on the Austrian-Hungarian border in 1732, the son of a wagon maker. He was raised essentially as a peasant (a heritage reflected in the later character of his minuets particularly), but with the hope that he might become a clergyman. His studies at nearby  Hainburg included lessons on wind and string instruments, and his musical gifts were quickly evident. In an autobiographical sketch, Haydn remembered his childhood as "more floggings than food" and without proper teaching. But he listened to everything around him, and "thus little by little my knowledge and ability were developed." Haydn was not a prodigy like Mozart, Schubert, or Mendelssohn, but he had an even, balanced, and highly industrious temperament that served him well and fit comfortably with the era in which he was born.

Hainburg included lessons on wind and string instruments, and his musical gifts were quickly evident. In an autobiographical sketch, Haydn remembered his childhood as "more floggings than food" and without proper teaching. But he listened to everything around him, and "thus little by little my knowledge and ability were developed." Haydn was not a prodigy like Mozart, Schubert, or Mendelssohn, but he had an even, balanced, and highly industrious temperament that served him well and fit comfortably with the era in which he was born.

At the age of eight, Haydn was recruited into the choir of St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna, where he excelled until 1749 when his boy soprano voice broke, and he was expelled. Until 1758, he lived an impoverished freelance life, meanwhile studying the music of C.P.E. Bach and taking a few composition lessons. By his own admission, for eight years Haydn, who was "a wizard on no instrument...eked out a wretched existence." Slowly, though, his reputation grew, and in 1758 he became the music director and composer for Count von Morzin. Two years later he married Maria Anna Keller, the daughter of a hairdresser. This was a mistake. She did not like music, was a spendthrift, ill-tempered, and basically a shrew. Haydn later rationalized his extramarital affairs, telling his first biographer, "My wife was unable to bear children, and for this reason I was less indifferent toward the attraction of other women."

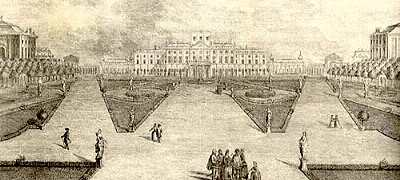

In 1761, Haydn entered the service of the Esterhazy family as vice-Kapellmeister. It was an event that would have ramifications for the history of music. Prince Paul Esterhazy was succeeded by Prince  Nicholas, the Magnificent, who in turn built a new palace second only to Versailles. Nicholas was an ardent music lover and the new palace had a 400-seat theater for opera. When Kapellmeister Gregorious Werner died, Haydn succeeded him, now fully presiding over a good-sized orchestra of between twenty and twenty-three players while conducting from the keyboard or violin. It became one of the best ensembles in Europe and was the workshop in which Haydn would continually experiment. The majority of his 104 symphonies (Symphony No.94 "Surprise:" Finale) were composed during this period.

Nicholas, the Magnificent, who in turn built a new palace second only to Versailles. Nicholas was an ardent music lover and the new palace had a 400-seat theater for opera. When Kapellmeister Gregorious Werner died, Haydn succeeded him, now fully presiding over a good-sized orchestra of between twenty and twenty-three players while conducting from the keyboard or violin. It became one of the best ensembles in Europe and was the workshop in which Haydn would continually experiment. The majority of his 104 symphonies (Symphony No.94 "Surprise:" Finale) were composed during this period.

Duties at the court included the business management of the court's musical life, as well as supplying music for the 2 to 4 p.m. weekly Tuesday and Thursday afternoon concerts. Prince Esterhazy played the baryton, a now obsolete cello-like hurdy-gurdy, and Haydn wrote for him approximately 200 trios with viola and cello as well numerous Baryton duos. In addition, Haydn authority H.C. Robbins Landon estimates that Haydn conducted 1026 performances of Italian operas alone between 1780 and 1790. Needless to say, his musical life was a full one, but he also had a good salary, a secretary, a maid, a coachman, and time for hunting and fishing. Regardless of his elevated position, Haydn preferred the company of his own class to intimacies with the aristocracy and was quite content with essentially being a well-paid and appreciated servant.

Haydn was confidently aware of his increasing stature in the greater world. Indeed, he was in no way threatened but rather deeply impressed by his only true competition, Mozart, who he considered "the greatest composer the world possesses now." They met in 1781 when Mozart was twenty-five, and the respect and influence were mutual, with Mozart dedicating his important set of string quartets (nos.14-19) to Haydn.

In 1790, Nicholas died and his successor, Anton, while retaining Haydn, greatly diminished the court's musical activities. Haydn was free to move to Vienna, and later in the year, he accepted an offer from violinist and impresario Johann Saloman to go to England. London was Europe's most active musical center at this time, and Haydn stayed for eighteen months while enjoying great public acclaim. Here he began his last set of twelve symphonies, received an honorary degree from Oxford, and had a liaison with the widow of a well-known pianist.

The trip being so successful, Haydn returned to London in 1794 staying through August 1795. The now completed group of symphonies became known collectively as the London symphonies, the last, No.104 being called individually the "London Symphony." By this time the Estarhazy orchestra had been restored by Nicholas II to mainly accompany church services and Haydn resumed his leadership and composing his series of great masses. This was also the time when he felt Austria should have an equivalent anthem to "God Save the King" and "God Save Emperor Franz" was the result. This famous melody can also be heard as the theme of the variations in the "Emperor Quartet" (Op.76, No.3).

In 1802, Haydn retired from his official duties. His wife had died in 1800, and he spent his last years without complaint, although suffering from rheumatism and various illnesses. As the respected elder of music, he apparently enjoyed receiving visitors and at his death on May 31, 1809, his last  words were, "Children be comforted. I am well." The Mozart requiem was played at his funeral.

words were, "Children be comforted. I am well." The Mozart requiem was played at his funeral.

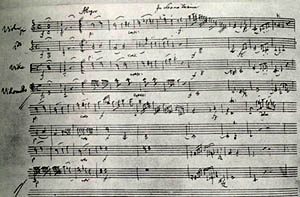

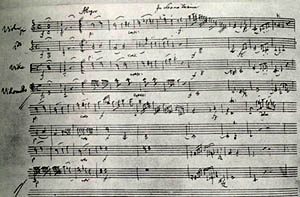

Franz Joseph Haydn was tremendously inventive and prolific. In addition to the Creation Mass, The Seasons, and 104 symphonies, there are 83 string quartets, 52 piano sonatas (No.3 in Eb, No.8 in D), and numerous other concertos and chamber pieces (Guitar Quartet in D: Allegro). Haydn may or may not have invented the string quartet itself, but he consolidated the nascent tendencies of Rococco music into the modern sonata principle, and this became the vehicle for the most ambitious elevated musical thoughts well into the next century and even into our own. With Haydn, as well as with Mozart and Beethoven, the sonata is, as Sir Donald Francis Tovey stated, a process, not a form. It changes dynamically and organically with the material and, like snowflakes, no two truly classical sonatas are alike.

Haydn was unburdened by the nineteenth-century idea of the artist and his historic legacy. He is one of the least neurotic of the great composers. Haydn treated composing more as an exalted craft in which he delighted in endlessly experimenting. A close look at his music reveals many daring gambits of harmony and form. His endless humor and wit are palpable, as is the warmth of his humanity. As Haydn once wrote, "Since God has given me a cheerful heart, He will forgive me for serving him cheerfully."

Biography by Allen Krantz. Copyright © Classical Archives, LLC. All rights reserved.

Hainburg included lessons on wind and string instruments, and his musical gifts were quickly evident. In an autobiographical sketch, Haydn remembered his childhood as "more floggings than food" and without proper teaching. But he listened to everything around him, and "thus little by little my knowledge and ability were developed." Haydn was not a prodigy like Mozart, Schubert, or Mendelssohn, but he had an even, balanced, and highly industrious temperament that served him well and fit comfortably with the era in which he was born.

Hainburg included lessons on wind and string instruments, and his musical gifts were quickly evident. In an autobiographical sketch, Haydn remembered his childhood as "more floggings than food" and without proper teaching. But he listened to everything around him, and "thus little by little my knowledge and ability were developed." Haydn was not a prodigy like Mozart, Schubert, or Mendelssohn, but he had an even, balanced, and highly industrious temperament that served him well and fit comfortably with the era in which he was born. Nicholas, the Magnificent, who in turn built a new palace second only to Versailles. Nicholas was an ardent music lover and the new palace had a 400-seat theater for opera. When Kapellmeister Gregorious Werner died, Haydn succeeded him, now fully presiding over a good-sized orchestra of between twenty and twenty-three players while conducting from the keyboard or violin. It became one of the best ensembles in Europe and was the workshop in which Haydn would continually experiment. The majority of his 104 symphonies (

Nicholas, the Magnificent, who in turn built a new palace second only to Versailles. Nicholas was an ardent music lover and the new palace had a 400-seat theater for opera. When Kapellmeister Gregorious Werner died, Haydn succeeded him, now fully presiding over a good-sized orchestra of between twenty and twenty-three players while conducting from the keyboard or violin. It became one of the best ensembles in Europe and was the workshop in which Haydn would continually experiment. The majority of his 104 symphonies ( words were, "Children be comforted. I am well." The Mozart requiem was played at his funeral.

words were, "Children be comforted. I am well." The Mozart requiem was played at his funeral.